Object Oriented Product

28 Apr 2024tl:dr

-

“Product” is a confused term - which causes problems - it lacks coherent and consistent meaning thus being either confusing or worse still impossible for companies trying to make great products and/or work at speed and scale.

-

Here’s why and how we got here - it’s a young (<20 years) discipline with one foot in the Agile Development Framework, one foot in the customer obsession needed for winning products and a head in the clouds (sic) of the companies that do both at speed and scale (M(F)AANG etc.)

-

Here’s a different way to think about it - it’s surprisingly useful to think about it using the principles of an approach to software engineering called Object Oriented Programming (OOP).

-

Why this might help - A lot of the confusion and implementation challenges resolve if we think of the ability to respond to changing requirements, agility and flexibility needed for great products as an emergent property of concepts like objects that encapsulate both data and the operations that manipulate them. This shift allows us to go beyond traditional functional approaches, also promoting modular design and reusability.

Intro and Warning:

- A longer piece that’s been kicking around for a while (hence, and apologies for, delay)

- Sundry jargon and multiple diagrams ahead

Context

Airbnb (Figma config23 Conference) : “… we got rid of the classic product management function. Apple didn’t have it either…”

The internet (especially designers): “Product management is dead!”

1k+ Apple Product Managers*: “We exist”

1m+ Product Managers*: “Is this about customer experience again?”

250k + Product Owners*: “Wait, what?”

(*current job title on LinkedIn)

Airbnb (some time later): “… well actually we kept the people, offloaded the programme management, combined it with marketing and called them something different… now they’re Product Marketers”

The internet: Wait, what?”

1. Problem - what is it and how is it done?

As suggested in the opening exchange, there can be a lot of confusion, tension and general fuzziness in discussions about product, product management and ownership - all the more surprising given the fact that well over 1m professionals on LinkedIn use it in their description of what they do.

One challenge is that when a word or concept is stretched to mean almost everything, it risks meaning nothing at all. As an excuse to include a favourite Aldous Huxley quote:

“Words can be like X-rays if you use them properly – they’ll go through anything… However, when words are overused or misused, they can become just background noise,…”

As somebody who has worked (inc. currently) in, at and on “product” (I’ll drop the quotation marks as the point is made) for more than a decade, what follows is a brief overview and review as I see it.

Product is invoked when discussing:

- A Mindset (https://medium.com/agileinsider/what-is-the-product-mindset-af06e01adf70)

- A Set of Capabilities valuable to a segment (https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary/product-digital-business)

- An Operating Model (https://www.svpg.com/the-product-operating-model/)

- A type of Engineer (https://blog.pragmaticengineer.com/the-product-minded-engineer/)

-

A Management Function (https://www.productplan.com/learn/what-is-product-management/)

- Building on the LinkedIn current job titles theme we also have a range of what could be considered specialised versions of existing functions or roles:

- Product Manager (form of business management?)

- Product Owner (form of scrum member)

- Product Engineer (form of developer/software Engineering?)

- Product Designer (form of design?)

- Product Marketing Manager (form of marketing?)

- Product Analyst (form of business analysis?)

- Product Support Specialist (form of customer support?)

- Product Co-ordinator (form of project management?)

- Product Strategy Director (form of Executive strategy?)

- etc.

So far, so confusing and so what? Everyone is working on some aspect of product and knows what they’re supposed to do - we’re all product companies now, why does it matter?

It matters because, as opposed to start-ups who continually obsess over product (outlined below in the Lean Startup) but can fail for adjacent, more interesting reasons - there are widely acknowledged challenges with introducing, transforming and executing product in legacy/scale enterprise. Today, many claim to have switched to a “Product Mindset vs Project Mindset” yet still manage to manifest many of the habitual dysfunctions and pathologies common to their type and most importantly have no real idea why the switch hasn’t delivered what was hoped for.

If no-one is quite sure what it means or understands exactly what product does, how do you introduce and manage it? - what are the necessary transformations - what needs to change? Why does executing a product driven approach not deliver great products faster?

As is obvious, this is often a complex multi-variate problem and way beyond the scope of one essay. However it is fair to say that the challenges with a less than twenty year old discipline began at it’s inception.

2. Causes

The origin can best be located 18 years ago (as of 2024) with Ken Norton in his essay “How to hire a product manager”:

Remember friend, nobody asked you to show up

Product management may be the one job that the organization would get along fine without (at least for a good while). Without engineers, nothing would get built. Without sales people, nothing is sold. Without designers, the product looks like crap.

But in a world without PMs, everyone simply fills in the gap and goes on with their lives. … Now, in the long run great product management usually makes the difference between winning and losing, but you have to prove it. Product management also combines elements of lots of other specialties — engineering, design, marketing, sales, business development.

As he points out in 2023, this should have been entitled ‘What is a Product Manager’ and was written at the same time as Google were establishing their associate product manager program. He then summarises the qualities and by so doing begins to define the specific view of the problem space that the product manager works in if not their exact role - other than to ensure winning products in the long run.

The reason to have product managers at all in this sense, was thus to ensure winning (great) products driven by the success (and ability to deliver at scale and speed) of those from companies similar to ones the author worked at (Yahoo then Google[Docs, Calendar, Maps and Ventures]).

The issue of whether product is a discrete thing was then elegantly side-stepped in the Lean Startup (Eric Ries - 2011) by articulating a set of five principles for entrepreneurs to create a successful startup (which means you have a winning product - albeit not at scale) basically by beginning with customers (interviews, research, discovery), building an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) then testing and iterating quickly.

The ‘build, measure, (validate) learn’ loop located product squarely in the language/domain of software development reflecting the established agile approach of sprints and increments of value for building software - see below for Agile. (NB this is I think resolved in the conclusion)

The drive to instantiate this way of working in non-startups (Scale-ups and Established Enterprise) continued. Marty Cagan’s book “INSPIRED: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love” (2018) has as it’s opening sales pitch:

“How do today’s most successful tech companies—Amazon, Google, Facebook, Netflix, Tesla—define, design and develop the products that have earned the love of literally billions of people around the world? Perhaps surprisingly, they do it very differently than the vast majority of tech companies.”

This at the time when a wider range of businesses were realising that by becoming ‘Digital’ they were de facto moving towards being a technology (if not a software) company. Naturally they then adopted a top down functional approach to organise and deliver.

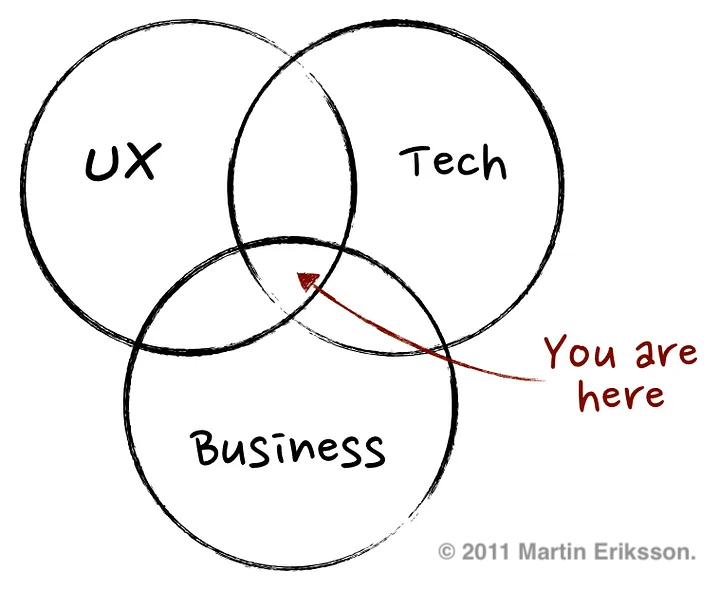

Not surprisingly many diagrams followed, most famously Martin Eriksson, product leader and founder of ProductTank in 2011 initially summed up product management using a simple Venn diagram that sits the product manager at the intersection of business, technology, and user experience.

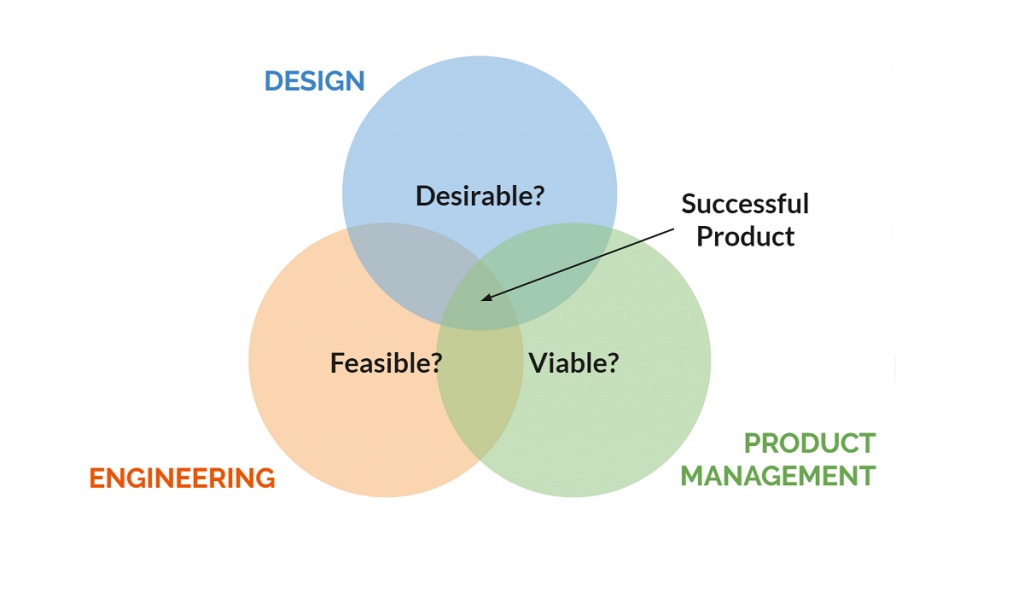

Another view:

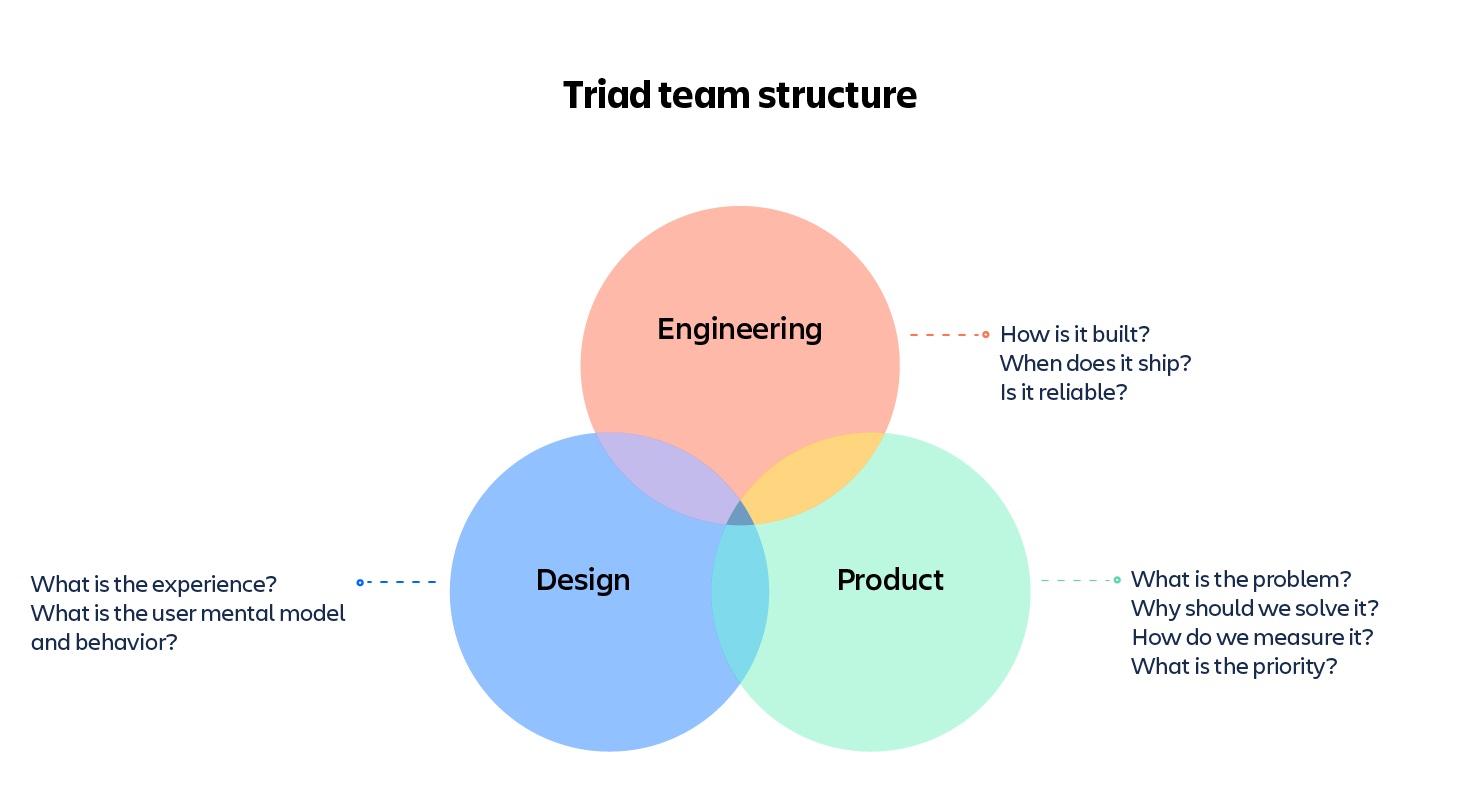

Further versions followed - notably the Atlassian Triad Model centering Product Management in the “Business” role which moved it away from Engineering and in some ways made sense.

Made sense because, since the early 2000’s the job of focusing on the business side of product development and spending the majority of their time liaising with stakeholders and the software engineering team had been elsewhere enshrined in the scrum team member called a Product Owner. (It almost certainly pre-dated 2000 as it was part of the Scrum Framework launched by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland).

In Scrum, the notion of “ownership” stems from the role’s obligation to be solely accountable for maximizing the value of the product under development. The Scrum Guide says, in part:

The Product Owner is the sole person responsible for managing the Product Backlog…The Product Owner is one person, not a committee…For the Product Owner to succeed, the entire organization must respect his or her decisions.

So, Product Manager == Product Owner?

Well, no. As the Ken Norton article/ Google experience from 2006 suggest, teams with Product Owners didn’t always build winning products or at least could satisfy their roles where value was predominantly the delivery of working software.

In general and for reference, Pendo’s 2019 report based on an aggregation of anonymized product usage data suggested that “80 percent of features in the average software product are rarely or never used” - further, “publicly-traded cloud software companies collectively invested up to $29.5 billion developing these features, dollars that could have been spent on higher value features and unrealized customer value”.

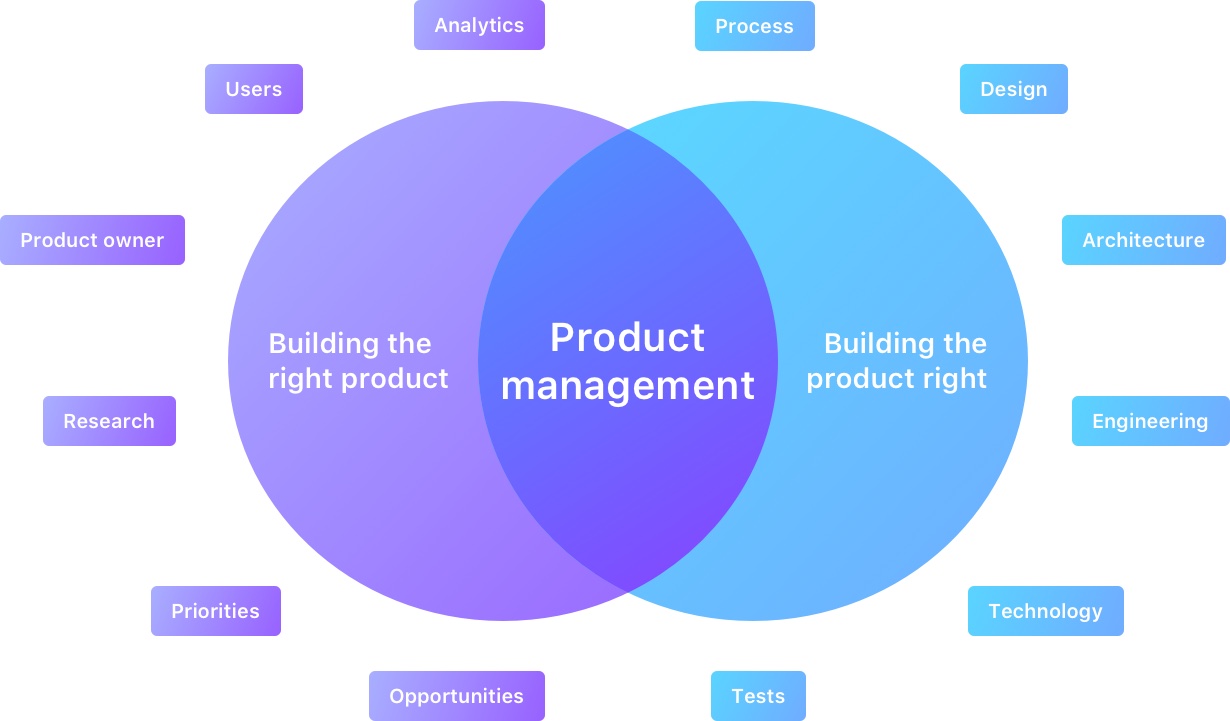

Product Management was still seen as the balancing act between building stuff right and building the right stuff.

Of course we can show the roles and relationship in yet another diagram:

This helps but still doesn’t address the ‘fuzziness’ around the specific function of product nor how to approach delivery.

Product could clearly be represented as an open system with an output (Customer outcomes), comprising elements, interconnections, flows, feedback loops, leverage points etc.

Putting it together as a system of interconnected ‘black boxes’ such as Engineering, Business or even a level down toward a more gears-like (deterministically interconnected) understanding comprising Architecture, Research, Analytics etc. gets us so far but of course specifying exactly how these drive each other and which ‘black box’ they sit in, is where the complexity above begins necessitating a loose enough description or concept of Product that we could easily find ourselves at the beginning of this piece.

A systems view in increasing resolution (verbosity you say?) might be:

Product is a system of geared concepts oriented to delivering maximum value exchange between a company and it’s customer.

Geared concepts delivering a series of guided trade-offs executed to optimise the value exchange between a company and its actual or desired target customers.

Guided (by principles/approach) trade-offs (intersections) executed (processes and functions) to optimise the value exchange between a company and its actual or desired target (creating and keeping) customers.

(The irony is not lost on me that we can create a similar vague usage/challenge-response for what ‘value’ means but one rabbit hole at a time…)

This view contains many but not all of the (imho) important enough concepts. It can however also lead to discussions about wha constitutes value, what and how the trade-offs are plus how they are prioritised.

Before moving on it is worth mentioning that is an interesting development about there being two forms of Product Management – for two very different situations: feature teams vs product teams.

Very useful in so far as Product team > Feature team > Delivery team but we seem to still be in a world of defining functions or at least functional approaches.

The dilemma is well addressed in Melissa Perri’s book “Escape the Build Trap”:

“To stay competitive in today’s market, organizations need to adopt a culture of customer-centric practices that focus on outcomes rather than outputs. Companies that live and die by outputs often fall into the “build trap,” cranking out features to meet their schedule rather than the customer’s needs.”

Customer-centricity and outcome focus seems to be moving us back in the direction of the ‘core’ Lean Startup approach and the companies that embodied it.

With a slight shift in thinking this could represent the penultimate stage to what might be the best way of representing Product.

Perri’s follow up book Product Operations not only builds on this but with it’s focus on aligning daily operations with the broader product strategy, delineating the specific roles and responsibilities within product teams, feedback loops, data-driven decisions and scaleability echoes this essay.

The shift in thinking uses a model from a different discipline (perhaps not that different - we may just be adding to the Agile foundations borrowed from Software Development…) and can be surprisingly insightful.

3. A different way to think about it

(caveat - I wish to extend apologies in advance to CS graduates, IT professionals and fellow Hyperskill alumni where I first encountered the following..)

OOP (Object Oriented Programming)

At it’s simplest, OOP means trying to organise the code for your application or system into objects that model parts of your problem.

It was developed as a different approach to what is known as Procedural programming.

Below are some of the differences between procedural and object-oriented programming: (edited from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/differences-between-procedural-and-object-oriented-programming/)

| Procedural Oriented Programming | Object-Oriented Programming |

|---|---|

| 1. In procedural programming, the program is divided into small parts called functions. | In object-oriented programming, the program is divided into small parts called objects. |

| 2. Procedural programming follows a top-down approach. | Object-oriented programming follows a bottom-up approach. |

| 3. Adding new data and functions is not easy. | Adding new data and functions is easy. |

| 4. In procedural programming, overloading is not possible. | Overloading is possible in object-oriented programming. |

| 5. In procedural programming, the function is more important than the data. | In object-oriented programming, data is more important than function. |

| 6. Procedural programming is based on the unreal world. | Object-oriented programming is based on the real world. |

| 7. Procedural programming uses the concept of procedure abstraction. | Object-oriented programming uses the concept of data abstraction. |

| 8. Code reusability absent in procedural programming, | Code reusability present in object-oriented programming. |

| Examples: C, FORTRAN, Pascal, Basic, etc. | Examples: C++, Java, Python, C#, etc. |

Without provoking internecine wars, it should be remembered that procedural programming is widely used and many applications are not ‘object-oriented’ but simply written in imperative style.

This isn’t meant as a useful discussion of pro’s and con’s and I won’t be going anywhere near key concepts like Encapsulation, Abstraction, Inheritance or Polymorphism except by implication but some key themes stand out already from the table (even if not a directly similar usage) and suggest this is as a worthwhile model for thinking about product.

To close the definitions, a procedural style is best used when we have

- A very well specified problem

- Where the specification won’t change

- And we want a very fast running program.

In this case we may trade the maintainability for performance.

Even in this statement we can begin to recognise assonance in some of the previous dissonance.

4. Why this helps

How often do we feel we have laser clear focus on a problem with unchanging specifications? Is enterprise structure and scale tilted toward performance or maintainability? Defining or implementing product with a procedural design model would seem like an anti-pattern

Picking just four of the key ideas in the table to expand thematically:

-

Objects vs Functions

This is more than just different names for the same thing. Objects contain both data (attributes) and behaviour (methods) that describe their characteristics and actions. Functions take inputs and produce outputs - they are immutable and avoid shared states.

One way of thinking about is to consider the assumed non-overlap of some of the job titles mentioned in outlining the Problem. Do they really exist to do different things without changing the same data?

-

Bottom up vs Top Down

Working with outcomes rather than outputs - each object is identified first. This means we can make decisions about reusable low-level utilities then decide how these will be put together to create a high-level construct.

One way of thinking about this is the possibility for end to end delivery of pieces of customer value. Ideally this owned by one cross-functional team but is often impossible due to the top down construct.

-

Real world vs Unreal world

Reflecting the realities of the problem space - we see the similarities between things that we label with a class. We don’t see the class itself but instances of it. Most importantly we’re structuring our approach based on how things are, not how they should be or we think they might be.

An obvious way of thinking about this might be personas but there is an even better start point in considering exactly what the customer is trying to achieve (Job to Be Done) as the real world.

-

Data > Function

Providing a simplified and generalized view of data objects or structures - we hide the implementation details of the data and emphasizes the essential properties and behaviors. Objects manage their own data and expose only necessary functionalities to the outside world

This is quite natural considering points 1 - 3 and a way of thinking about this not only ensures being data-driven but also how we use and measure the data that drives customer outcomes rather than vanity metrics or an approach such as OKRs.

It seems fair to suggest that there’s enough substantive similarity here to indicate more than an over-stretched metaphor?

Overall, object-oriented programming is a tool to architect code that mirrors the intricacies of the real-world, enabling us to create valuable applications while maximizing agility. As a final point, it’s particularly useful when refactoring code written in a procedural style.

In other words, start-ups, fintechs etc. are often natively built this way whilst trying to adapt an existing structure calls for some version of this approach.

A product mindset then, is not a fintech/skunkwork/innovation lab nor is it an oversupply of foosball tables, post-it notes, kanban boards and applying the ‘Product’ qualifier to existing functions or roles albeit that these are an important nod to the principles and practice of Lean Startup, Agile delivery and customer obsession.

However we would be better off looking to understand where procedural patterns have been, or are being, applied and trying to switch how the application (or system) works to Object Orientation.

So, to deliver winning products - create better customer outcomes by

-

modelling the real world problem space

-

thinking objects, methods and data rather than functions

-

structure, execute and measure accordingly

Most importantly notice switches from one building pattern to the other.

At least then some of the job titles might make more sense.